|

While our images are electronically watermarked, the antique prints themselves are not.

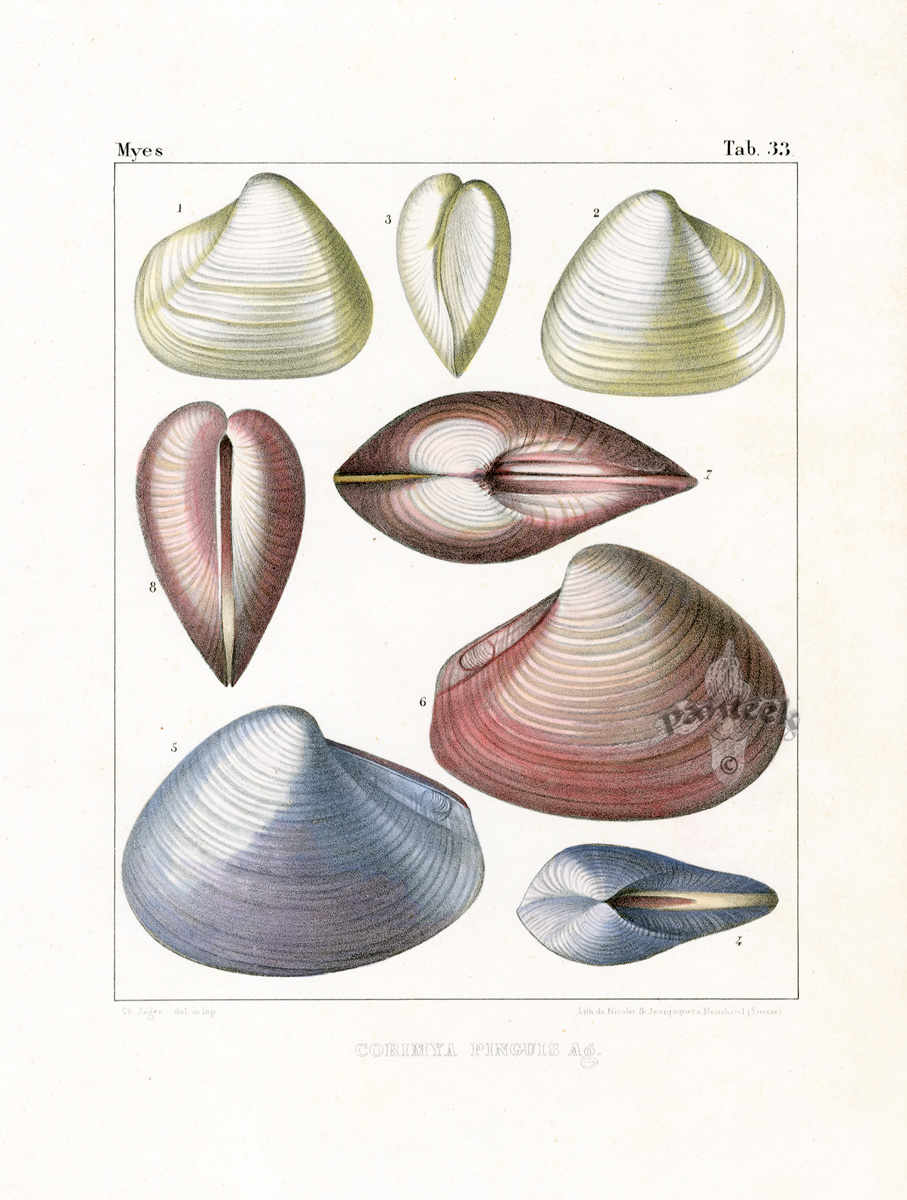

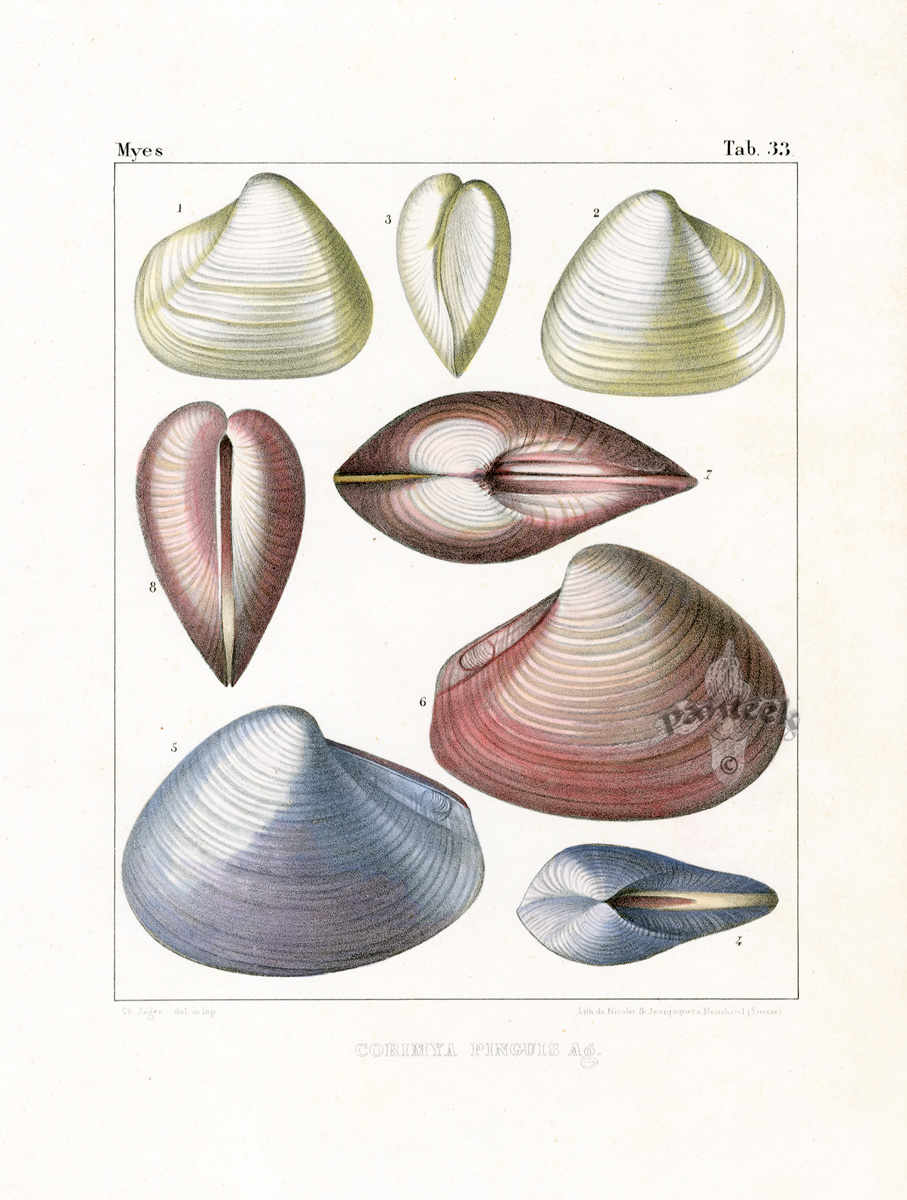

Corimya Pinguis AGZ33 $65

The singles prints measure

approximately 9 inches by 12 inches

Louis Agassiz, (born May 28, 1807, Motier, Switz.—died

December 14, 1873, Cambridge, Mass., U.S.), Swiss-born

U.S. naturalist, geologist, and teacher who made

revolutionary contributions to the study of natural

science with landmark work on glacier activity and

extinct fishes. He achieved lasting fame through his

innovative teaching methods, which altered the character

of natural science education in the United States.

Agassiz was the son of the Protestant pastor of Motier, a village on the shore of Lake Morat, Switzerland. In boyhood he attended the gymnasium in Bienne and later the academy at Lausanne. He entered the universities of Zürich, Heidelberg, and Munich and took at Erlangen the degree of doctor of philosophy and at Munich that of doctor of medicine.

As a youth he gave some attention to the ways of the brook fish of western Switzerland, but his permanent interest in ichthyology began with his study of an extensive collection of Brazilian fishes, mostly from the Amazon River, which had been collected in 1819 and 1820 by two eminent naturalists at Munich. The classification of these species was begun by one of the collectors in 1826, and when he died the collection was turned over to Agassiz. The work was completed and published in 1829 as Selecta Genera et Species Piscium. The study of fish forms became henceforth the prominent feature of his research. In 1830 he issued a prospectus of a History of the Fresh Water Fishes of Central Europe, printed in parts from 1839 to 1842.

The year 1832 proved the most significant in Agassiz’s early career because it took him first to Paris, then the centre of scientific research, and later to Neuchâtel, Switz., where he spent many years of fruitful effort. While in Paris he lived the life of an impecunious student in the Latin Quarter, supporting himself and helped at times by the kindly interest of such friends as the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt—who secured for him a professorship at Neuchâtel—and Baron Cuvier, the most eminent ichthyologist of his time.

Already Agassiz had become interested in the rich stores of the extinct fishes of Europe, especially those of Glarus in Switzerland and of Monte Bolca near Verona, of which, at that time, only a few had been critically studied. As early as 1829 Agassiz planned a comprehensive and critical study of these fossils and spent much time gathering material wherever possible. His epoch-making work, Recherches sur les poissons fossiles, appeared in parts from 1833 to 1843. In it, the number of named fossil fishes was raised to more than 1,700, and the ancient seas were made to live again through the descriptions of their inhabitants. The great importance of this fundamental work rests on the impetus it gave to the study of extinct life itself. Turning his attention to other extinct animals found with the fishes, Agassiz

published in 1838–42 two volumes on the fossil

echinoderms of Switzerland.

From 1832 to 1846 he served as professor of natural history in the University of Neuchâtel. In Neuchâtel he acted for a time as his own publisher, and his private residence became a hive of activity with numerous young men assisting him. He now began his Nomenclator Zoologicus, a catalog with references of all the names applied to genera of animals from the beginning of scientific nomenclature, a date since fixed at Jan. 1, 1758.

Agassiz is remembered today for his theories on ice ages, and for his resistance to Charles Darwin's theories on evolution, which he kept up his entire life. He died in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1873 and was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, joined later by his wife. His monument is a boulder selected from the moraine of the glacier of the Aar near the site of the old Hôtel des Neuchâtelois, not far from the spot where his hut once stood; and the pine-trees that shelter his grave were sent from his old home in Switzerland.

The son of a minister, Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz was born on May 28, 1807 in the village of Môtier, in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Agassiz was educated in the universities of Switzerland and Germany as a physician, like many naturalists of the time. He studied with prominent German biologists, including Oken and Döllinger. These men were followers of Naturphilosophie, a German Romantic philosophy that sought metaphysical correspondences and interconnections within the world of living things. Though Agassiz later renounced this philosophy, he was never quite able to free himself from its influence. Receiving his medical degree from the University of Erlangen in 1830, he went to Paris on December 16, 1831 to study comparative anatomy under Cuvier, the most famous naturalist in Europe. Cuvier was so impressed with Agassiz's work on fossil fishes that he turned over to Agassiz his own notes and drawings for a planned work on fossil fishes. Cuvier died on May 13, 1832, yet although their relationship lasted only months, Agassiz always considered himself an intellectual heir of Cuvier. For the rest of his life, Agassiz promoted and defended Cuvier's geological views and his classification of the animals. With the publication of his vast work on the fossil record of fishes, Poissons fossiles, Agassiz's reputation began to grow in the scientific community.

After Cuvier's death, Agassiz took up a professorship at the Lyceum of Neuchatel in Switzerland, where for thirteen years he worked on many projects in paleontology, systematics, and glaciology. Agassiz took up the study of glaciers in 1836 and was guided by colleagues Ignatz Venetz and Jean de Charpentier to examine the geological features of his native Switzerland. Agassiz noticed the marks that glaciers left on the Earth: great valleys; large glacial erratic boulders carried long distances; scratches and smoothing of rocks; mounds of debris called moraines pushed up by glacial advances. He realized that in many places these signs of glaciation could be seen where no glaciers existed. Previous scientists had variously explained these features as made by icebergs or floods, but following the lead of others, Agassiz became a powerful proponent of the theory that a great Ice Age had once gripped the Earth, and published his ideas in Étude sur les glaciers in 1840. His later book, Système glaciare (1847), presented further evidence for this theory, gathered all over Europe. Agassiz later found even more evidence of glaciation in North America.

Agassiz was no evolutionist; in fact, he was probably the last reputable scientist to reject evolution outright for any length of time after the publication of The Origin of Species. Agassiz saw the Divine Plan of God everywhere in nature, and could not reconcile himself to a theory that did not invoke design. He defined a species as "a thought of God."

As he wrote in his Essay on Classification:

The combination in time and space of all these thoughtful conceptions exhibits not only thought, it shows also premeditation, power, wisdom, greatness, prescience, omniscience, providence. In one word, all these facts in their natural connection proclaim aloud the One God, whom man may know, adore, and love; and Natural History must in good time become the analysis of the thoughts of the Creator of the Universe …."

Agassiz was a staunch creationist; he taught that after every global extinction of life God created every species anew. This differed from the view of Cuvier, who recognized extensive and sometimes apparently quite abrupt changes in fossil faunas and their environments. Cuvier

did not think that God re-created life; he thought that

new species migrated in from elsewhere as climates and

environments changed. In 1840 he issued this work titled Études critiques sur les mollusques

fossiles.

No title page or frontispiece available with this

work. Excellent condition. Later hand coloring. On fine

wove paper.

We accept credit cards & PayPal. Florida residents pay Florida sales tax. Shipping for this item is $8.95. Items can be combined to save on postage. International shipping

starts at $30 and buyers are responsible for all customs duties

and fees. Our environment is smoke free. We pack professionally using only new materials. All items are beautifully wrapped and suitable for sending directly as gifts. You may return any item within 7 days if not satisfied. To order, you may call us at 1-888-PANTEEK, fax or email.

|